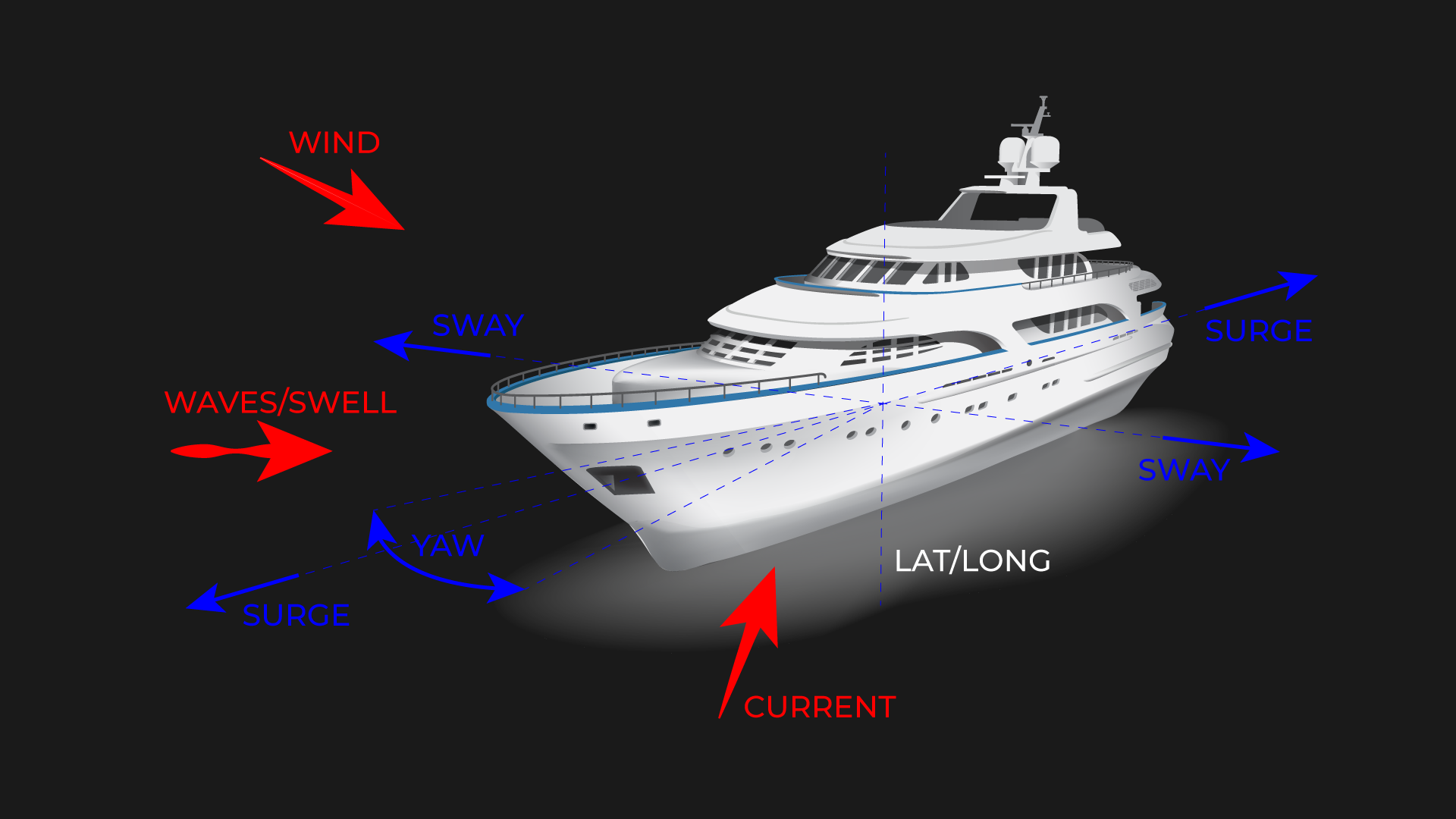

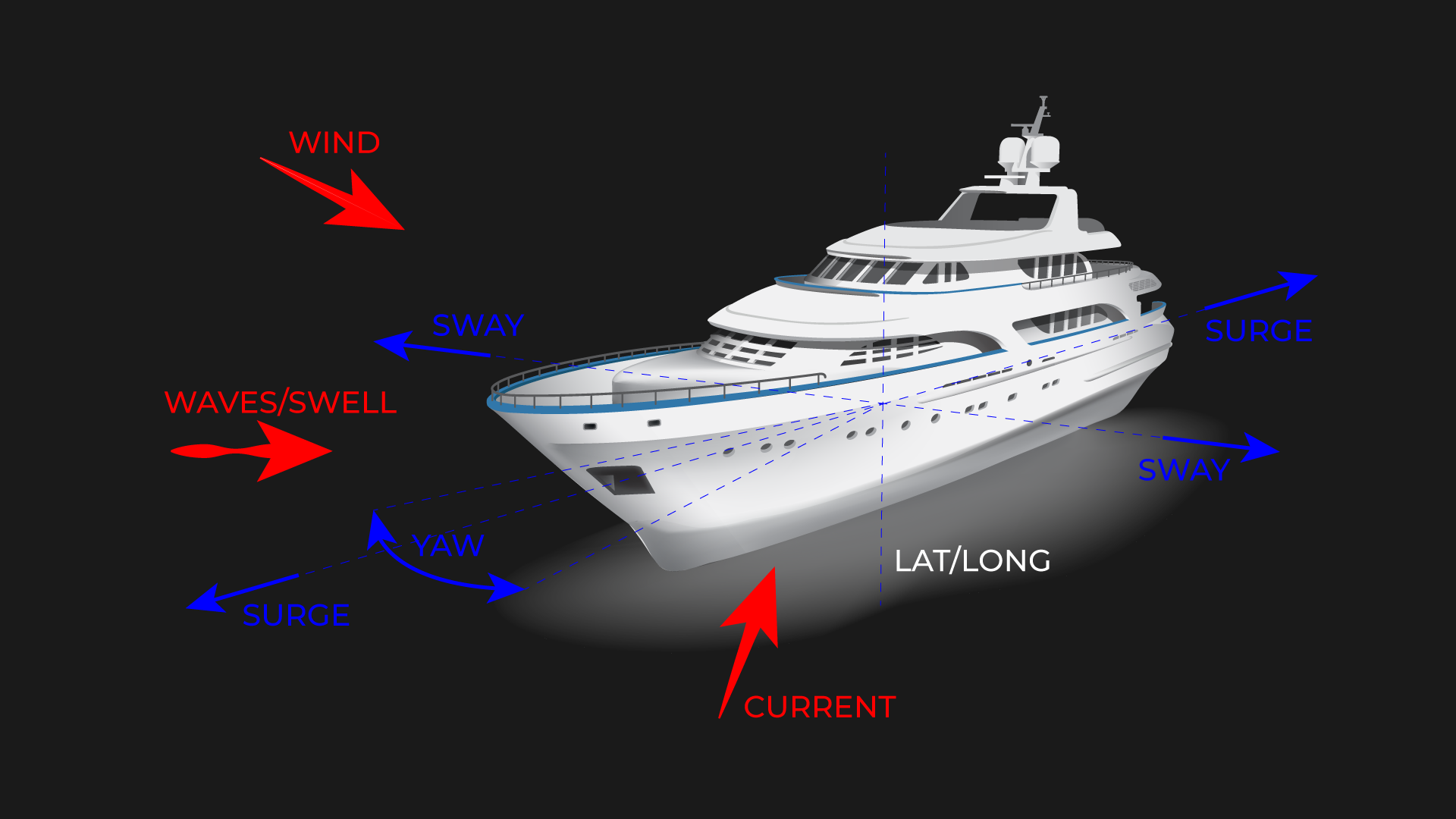

Electronic Anchoring vs. Dynamic Positioning, What’s The Difference?

I was prompted to write this after I saw a recent press release stating a new 80m+ superyacht project had “electronic anchoring to protect sensitive

On this page you will find articles related to the superyacht industry.

Please feel free to contact me if you would like to comment or have any subject you would like to see covered.

Remember to SHARE if you find an article of value.

Welcome to OnlyCaptains readers, I have now moved most articles of interest to this site.

I was prompted to write this after I saw a recent press release stating a new 80m+ superyacht project had “electronic anchoring to protect sensitive

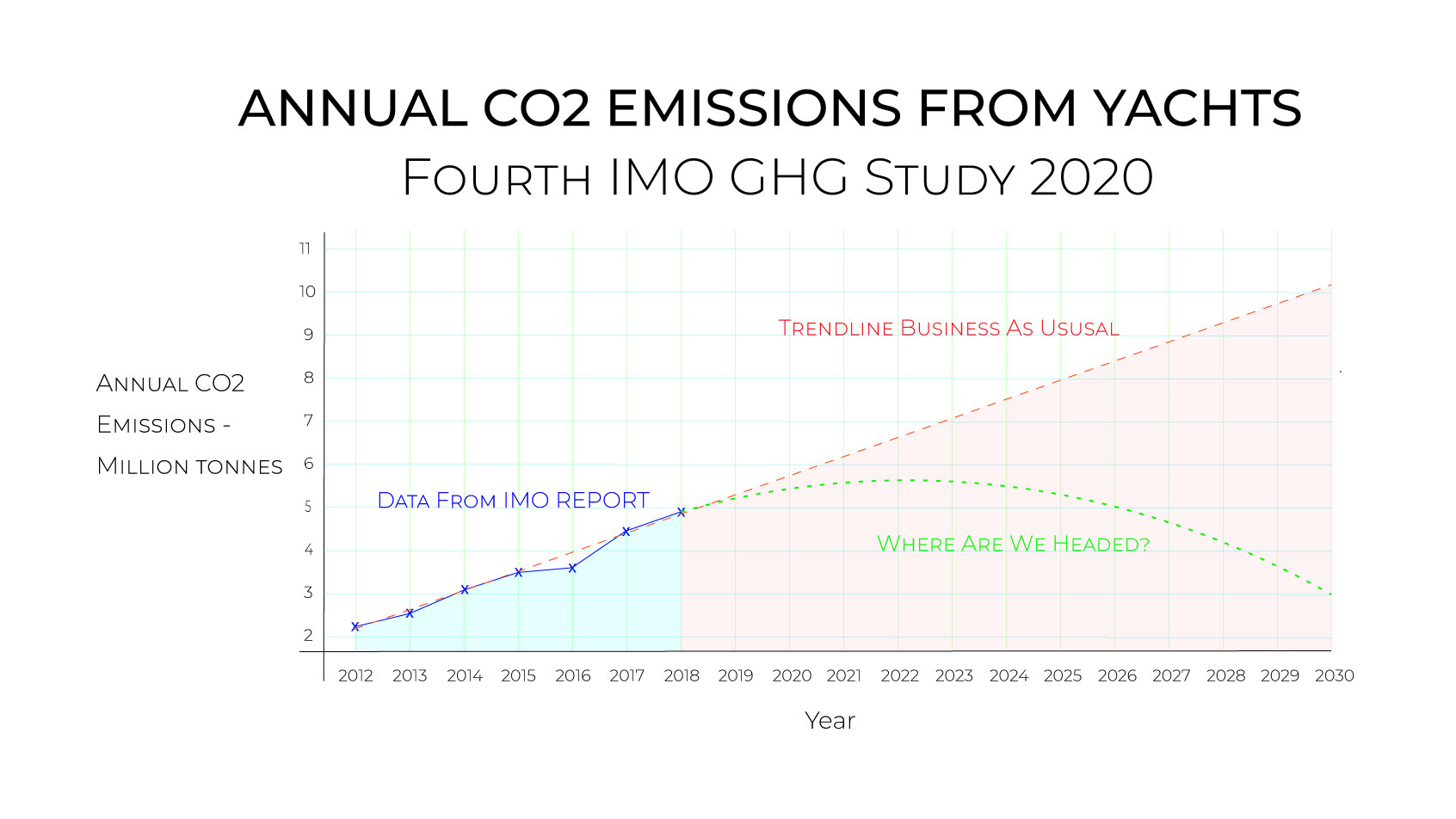

People often ask about the GHG emissions from superyachts and the ‘Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020’ provides some indicators for each year from 2012 –

There has been much talk about reducing CO2 emissions from superyachts and apart from incremental changes that may be possible through technology such as hybrid

There is a growing body of evidence that suggests a large percentage of the microfibres in our oceans is the result of washing clothes in automatic machines.

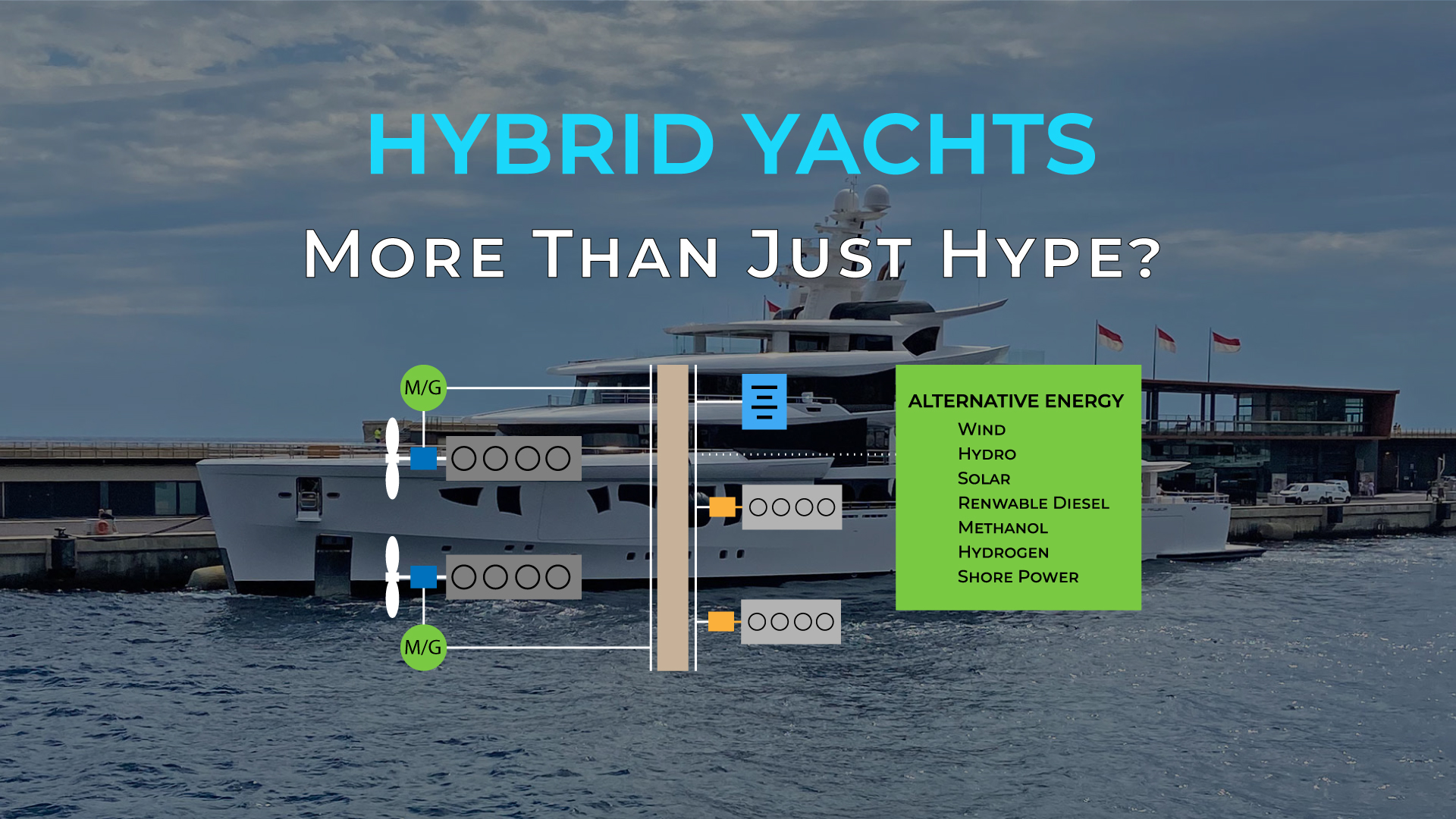

There has been a lot written about ‘Hybrid’ yachts, often with some hype about being eco-friendly, having green credentials, etc., but with very little information

There has been much debate about the quality of education and training for superyacht crew and, of course, the 3000gt limit. On the latter point,

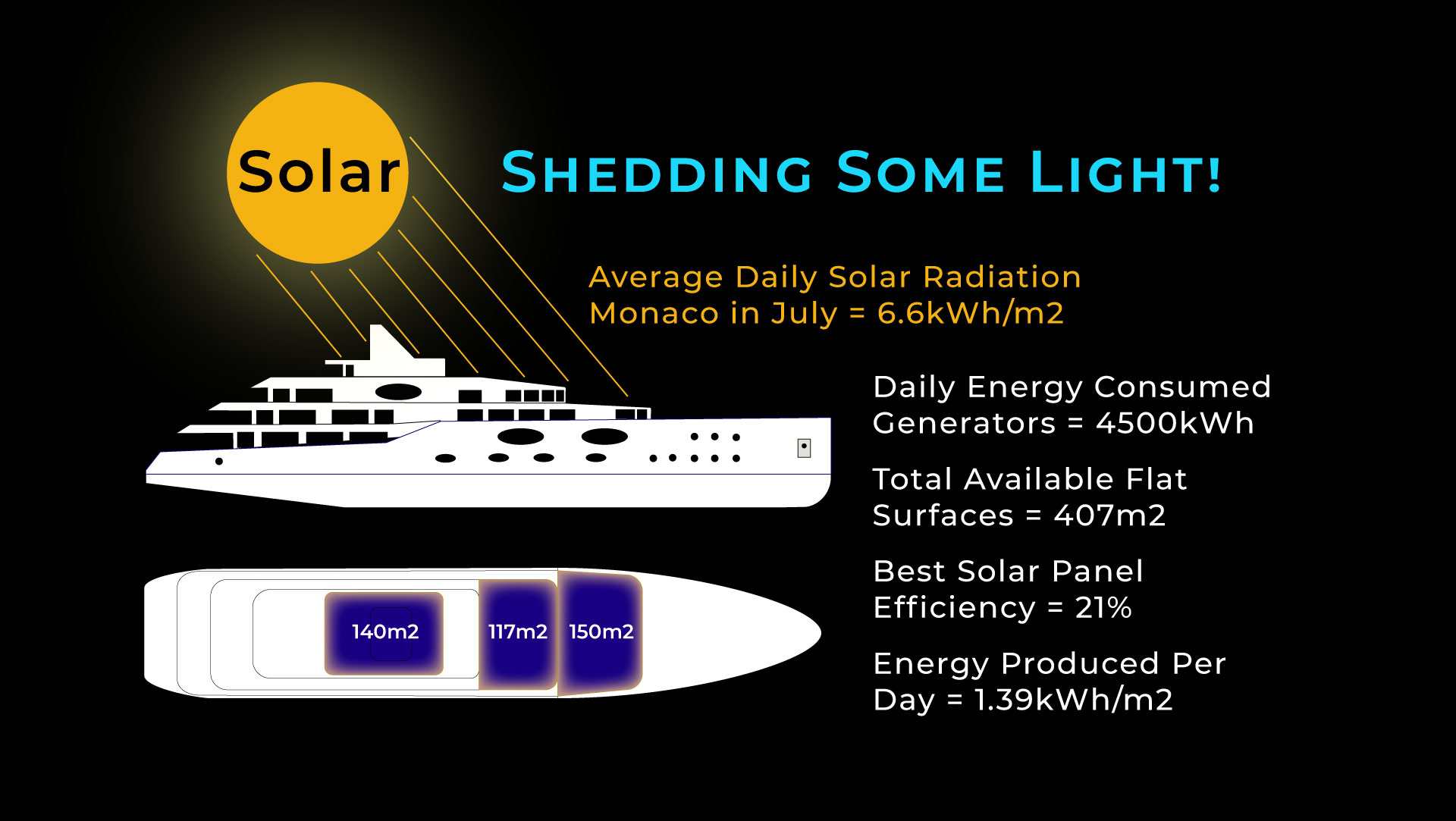

There have been several concepts, and a good many articles and discussions relating to the use of solar panels on superyachts. And, as a zero-emissions

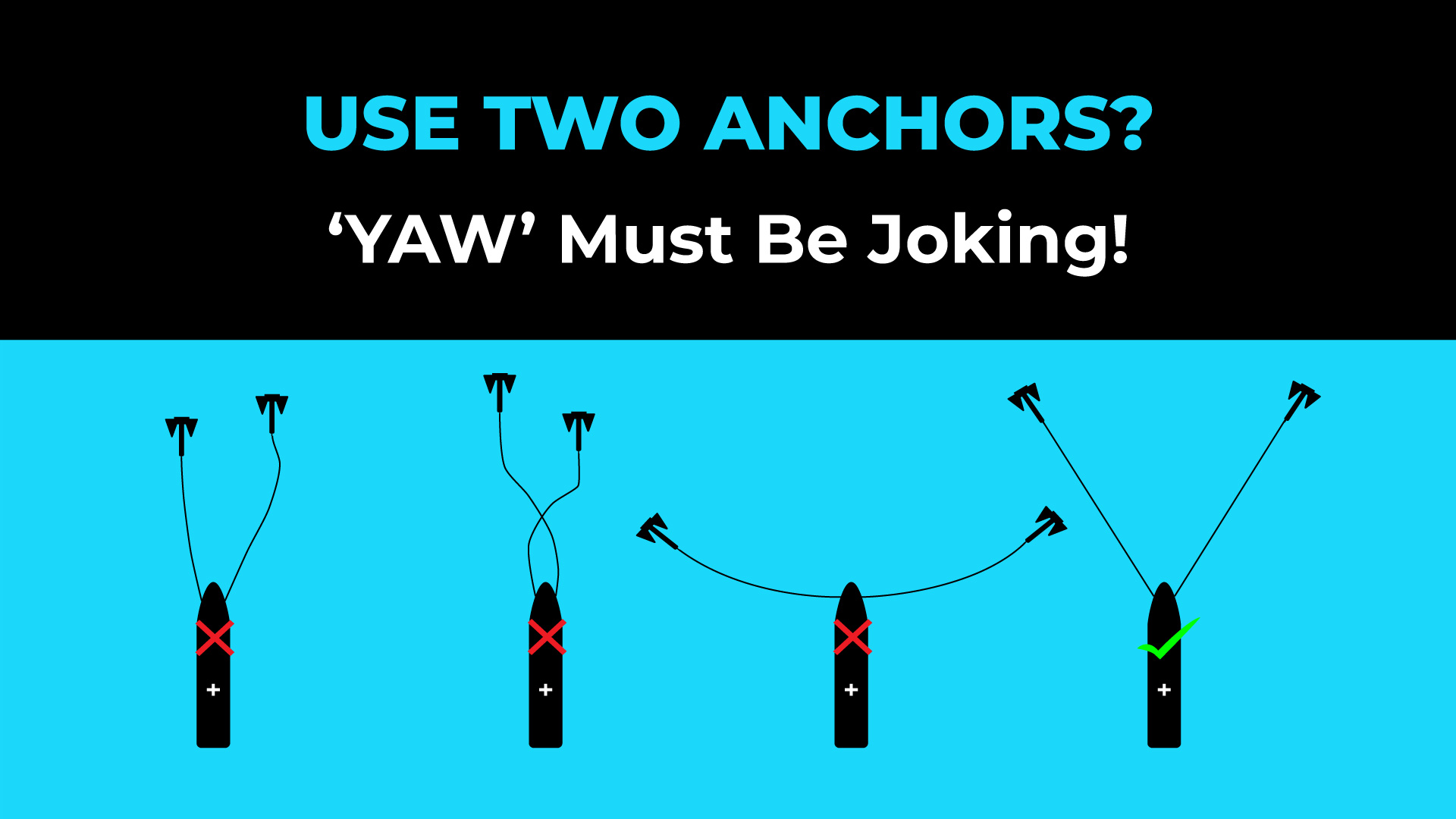

[Some Captains don’t like to use two anchors and, given some of my early experiences, I can understand the reluctance and the ‘you must be

Three Sixty Marine

Casabianca, 17 bd du Larvotto, Monaco.

info@threesixtymarine.com

Copyright 2021 Three Sixty Marine | All rights reserved